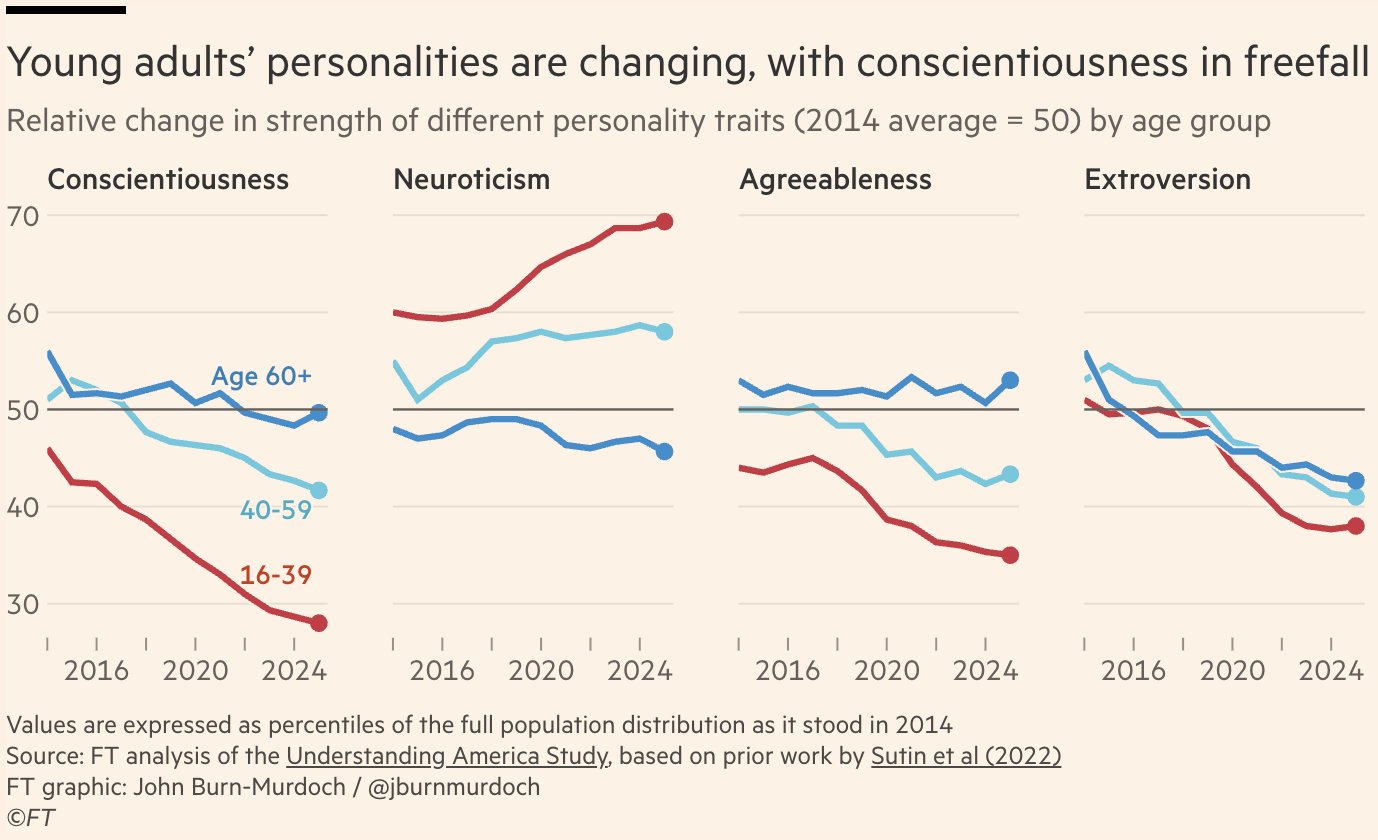

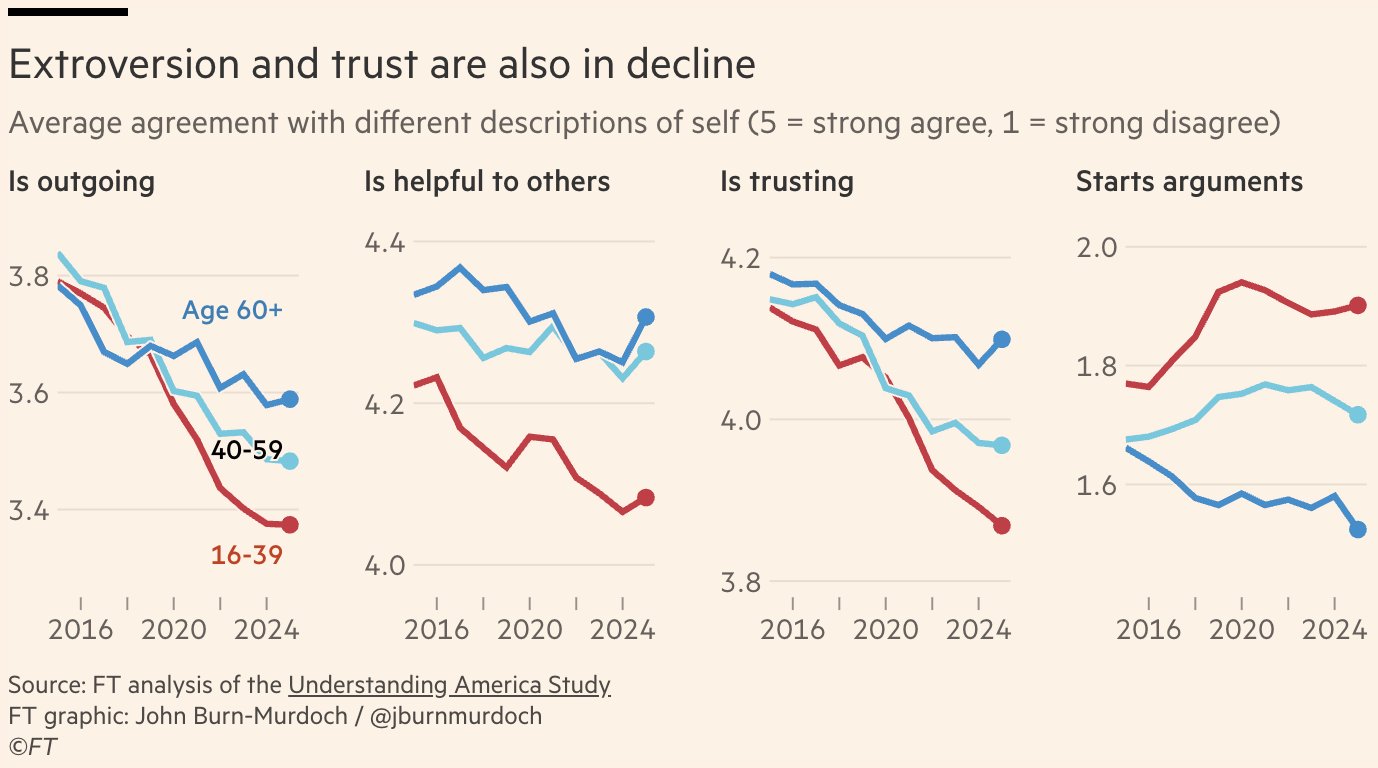

The always-excellent John Burn-Murdoch at the Financial Times has published a revealing piece with data showing that young people are becoming less conscientious, less outgoing, and less trustworthy—while also becoming more neurotic and more argumentative.

In the article, Burn-Murdoch tentatively points to smartphones, digital technologies, and the abundance of easy distractions as likely culprits.

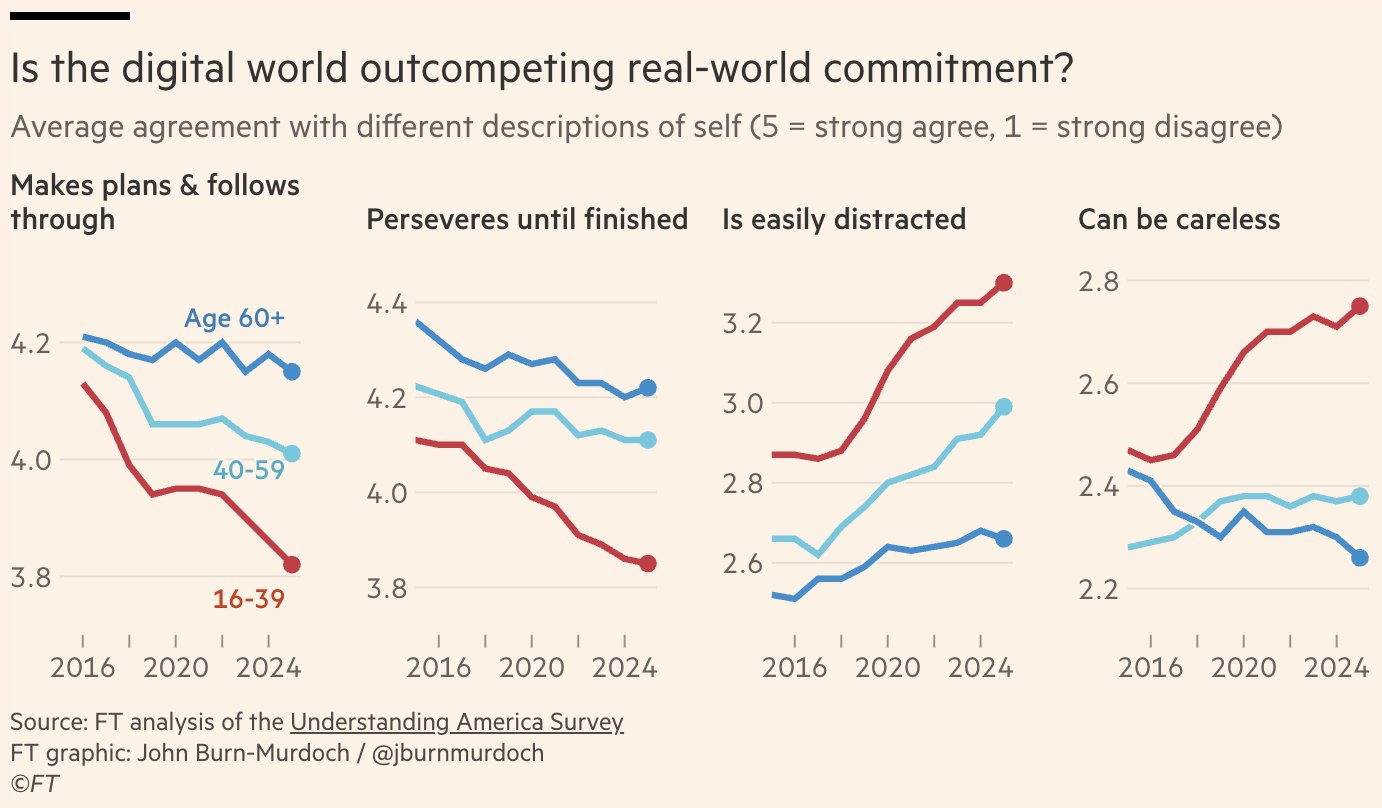

Digging deeper into the data, which comes from the Understanding America Study, we can see that people in their twenties and thirties in particular report feeling increasingly easily distracted and careless, less tenacious and less likely to make and deliver on commitments.

While a full explanation of these shifts requires thorough investigation, and there will be many factors at work, smartphones and streaming services seem likely culprits. The advent of ubiquitous and hyper-engaging digital media has led to an explosion in distraction, as well as making it easier than ever to either not make plans in the first place or to abandon them. The sheer convenience of the online world makes real-life commitments feel messy and effortful. And the rise of time spent online and the attendant decline in face-to-face interactions enable behaviours such as “ghosting”.

I’m a little hesitant to attribute all, or even a large part, of this depressing and worrying shift in people’s attitudes to digital technologies and smartphones—although I think they play a significant role. I suspect there are social, psychological, economic, and perhaps even spiritual dimensions to this.

Whenever people talk about the meaning crisis, I think this is, in essence, what they are referring to. It’s an area I’ve been trying to come to terms with, but I don’t yet have a clear enough understanding to articulate it fully.

The awesome Derek Thompson has been writing and speaking to experts on what smartphones are doing to us for a long time. So I went to his Twitter account and searched for “smartphone” and found some cool insights:

Technology-induced anxiety is not new:

Around the turn of the century, a nervous disorder first diagnosed in the U.S. gradually made its way across the Atlantic. The doctor George Miller Beard had called it “neurasthenia,” or nervous exhaustion. Europeans sometimes referred to it as “American Nervousness.” According to Beard, the affliction was most common among “the in-door classes of civilized countries” and the sufferers could be found “in nearly every brain-working household.”3

As Blom points out, those afflicted tended to be white-collar workers working at the “frontiers of technology,” as “telephone operators, typesetters on new, faster machines, railway workers, engineers, [or] factory workers handling fast machines. One 1893 hospital survey of neurasthenia found that among nearly 600 cases, “there were almost 200 businessmen, 130 civil servants, 68 teachers, 56 students and eleven farmers.” Notably, no manual workers were counted at the clinic. Neurasthenia seemed to disproportionately affect white-collar workers, who were “overwhelmed” by their labor. “Overwork was a common theme in patients’ histories,” Blom writes.

Smartphone Bans, Student Outcomes and Mental Health:

How smartphone usage affects well-being and learning among children and adolescents is a concern for schools, parents, and policymakers. Combining detailed administrative data with survey data on middle schools’ smartphone policies, together with an event-study design, I show that banning smartphones significantly decreases the health care take-up for psychological symptoms and diseases among girls. Post-ban bullying among both genders decreases. Additionally, girls’ GPA improves, and their likelihood of attending an academic high school track increases. These effects are larger for girls from low socio-economic backgrounds. Hence, banning smartphones from school could be a low-cost policy tool to improve student outcomes.

What Experts Really Think About Smartphones and Mental Health.

Are Smartphones Really Driving the Rise in Teenage Depression?

Why White-Collar Workers Spend All Day at the Office:

If the operating equipment of the 21st century is a portable device, this means the modern factory is not a place at all. It is the day itself. The computer age has liberated the tools of productivity from the office. Most knowledge workers, whose laptops and smartphones are portable all-purpose media-making machines, can theoretically be as productive at 2 p.m. in the main office as at 2 a.m. in a Tokyo WeWork or at midnight on the couch.

As Leamer and Fuentes write in the paper, “The innovations in personal computing and internet-based communications have allowed individual workers the freedom to choose weekly work hours well in excess of the usual 40.”

Why American Teens Are So Sad:

“I tell parents all the time that if Instagram is merely displacing TV, I’m not concerned about it,” Steinberg told me. But today’s teens spend more than five hours daily on social media, and that habit seems to be displacing quite a lot of beneficial activity. The share of high-school students who got eight or more hours of sleep declined 30 percent from 2007 to 2019. Compared with their counterparts in the 2000s, today’s teens are less likely to go out with their friends, get their driver’s license, or play youth sports.

The pandemic and the closure of schools likely exacerbated teen loneliness and sadness. A 2020 survey from Harvard’s Graduate School of Education found that loneliness spiked in the first year of the pandemic for everyone, but it rose most significantly for young people. “It’s well established that what protects teens from stress is close social relationships,” Steinberg said. “When kids can’t go to school to see their friends and peers and mentors, that social isolation could lead to sadness and depression, particularly for those predisposed to feeling sad or depressed.”

What Kids Told Us About How to Get Them Off Their Phones.

John’s twitter 🧵:

Interesting comments from the ever awesome Kyla Scanlon:

Also reminds me of something I heard on Derek Thompson’s Plain English podcast:

But maybe there is sort of an either-or dynamic with risk assets where either money is flowing into housing or stocks, but not both, because you can only sort of be caught up in one mania at a time.both because you can only sort of be caught up in one media at a time.Yeah.Yeah.I mean, there’s a sociological layer to this as well, which is that, you know, not to be a classic middle-aged guy here, but, you know, you invest your money in housing, you’re investing in a community, you’re investing in a foundation for building a family.You put that same amount of money into crypto and meme coins, you’re doing something very different.

You’re putting not only your attention into very different fields, you’re also delaying the year at which you begin to maybe start a family.And there’s so much evidence showing that, you know, coupling rates have been delayed and, you know, age of first fertility has been delayed and overall fertility is going down.You know, it’s funny.I’ve been thinking about this take maybe for the Substack that’s like every social phenomenon is a housing phenomenon and a smartphone phenomenon.Like I think I want to call it like the home screen hypothesis.It’s like every single thing you want, are you interested in why Americans are having less sex? Are you interested in why Americans are socializing less?Why they’re partying less? Why they’re dating less? Why there’s higher anxiety?

You can tell a housing and or smartphone story about all of this.

Join the Conversation

Share your thoughts and go deeper down the rabbit hole