“Not yet,” says Conrad Irwin:

Will this change as models become more capable? Perhaps?? But I think it’s going to require a change in how models are built and optimized. Software engineering requires models that can do more than just generate code.

When a person runs into a problem, they are able to temporarily stash the full context, focus on resolving the issue, and then pop their mental stack to get back to the problem in hand. They are also able to zoom out and focus on the big picture, allowing the details to temporarily disappear, diving into small pieces as necessary. We don’t just keep adding more words to our context window, because it would drive us mad.

Another study which shows that the hype about AI coding tools needs to be tempered:

We previously found that experienced open-source developers were slowed down using early-2025 AI tools, even with models like Claude 3.7 Sonnet that can complete long-horizon eval tasks.

What separates real coding from SWE benchmark tasks? Was human input holding the AI back?

To investigate this, we put the same model (Claude 3.7 Sonnet) in an agent scaffold and had it attempt 18 tasks from two open-source repos in the RCT.We then scored its PRs with human-written tests, where it passed 38% of the time, and manual review, where it never passed.

Even when agents pass on all human-written test cases, we estimate that their implementations would take 20-30 minutes on average to get to a mergeable state—which represents about a third of the total time needed for an experienced developer to complete the tasks.

In conclusion, it seems that models are reasonably able to implement the core functionality of these tasks, but there are too many other requirements/objectives they need to satisfy (and they perform worse on these other metrics collectively).

Interesting paper from Google DeepMind researchers.

They trained a fine-tuned Personal Health Large Language Model (PH-LLM) fine-tuned for health applications using data from wearable devices. Despite the limitations of the study, the findings are interesting:

Professional Examinations: PH-LLM scored 79% on sleep medicine exams and 88% on fitness exams, exceeding the average scores of human experts (76% and 71%, respectively). The model’s performance improved most significantly on more difficult questions, suggesting that fine-tuning was effective and not just a result of memorizing pre-training data

Personalized Coaching: In a large-scale evaluation of 857 real-world case studies, PH-LLM’s performance was similar to human experts for fitness-related tasks. For sleep insights, PH-LLM showed significant improvement over the base Gemini model and received high-quality ratings, with the top score given 73% of the time. The fine-tuning process specifically improved the model’s ability to incorporate domain knowledge and personalize insights using user data for sleep-related tasks

Predicting Subjective Outcomes: The model was trained to predict subjective, self-reported sleep outcomes using a multimodal adapter that integrated daily sensor data. This approach outperformed text-only prompting methods (zero-shot and few-shot) and performed on par with specialized logistic regression models.

Discovered this easy way to run small LLMs (small LLM :p) on Android phones.

Geoffrey Hinton says humanity is toast:

Most AI experts believe that sometime in the next 5 to 20 years, we’ll create AI systems that are smarter than people — and eventually, much smarter. There are very few examples of something more intelligent being controlled by something less intelligent. In fact, the only example we really know is a mother being “controlled” by her baby. Evolution built maternal instincts into mothers to make that possible.

If we don’t find a way to build something similar into these alien beings we’re creating, we’ll be history.

But intelligence is only one part of what makes a being. We also need to ensure they have empathy toward us. The problem is, we don’t yet know how to do that — but evolution figured it out.

François Chollet on LLMs:

Frontier LLM have superhuman text-based world knowledge. Frontier image / video models have superhuman vision-based world knowledge (e.g. Genie).

But current frontier VLMs are still absolutely clown shoes. Why? Relative scarcity of image:text pairs (while there is plenty of text and plenty of images/video).

Diffusion of AI

Arvind Narayanan on how fast will AI be adopted:

I’ve said it a hundred times but I’ll keep saying it: AI adoption and behavior change are slow — and will stay slow — no matter how fast capabilities improve. The stat in the screenshot is worth pondering: nearly a year after the release of “thinking” models, only a tiny fraction of users were using them (until GPT-5’s automatic switcher quietly bumped the numbers).

This is exactly what we should expect. The dominant narrative is that AI is being adopted at unprecedented speed, but that’s based on how many people have tried it, ignoring how they are using it, for how long they use it each day, and how much they are getting out of it. Even lifesaving innovations take a long time to percolate through the population. This is a property of human behavior, not the technology in question, so we shouldn’t expect AI to be any different. (For more on this, see AI as Normal Technology.)

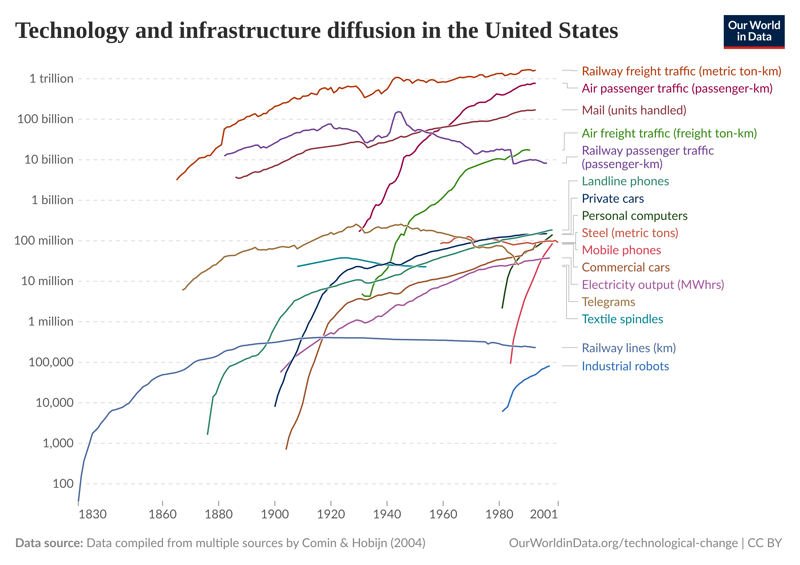

I googled “diffusion of different technologies” and found this paper. This image stood out to me:

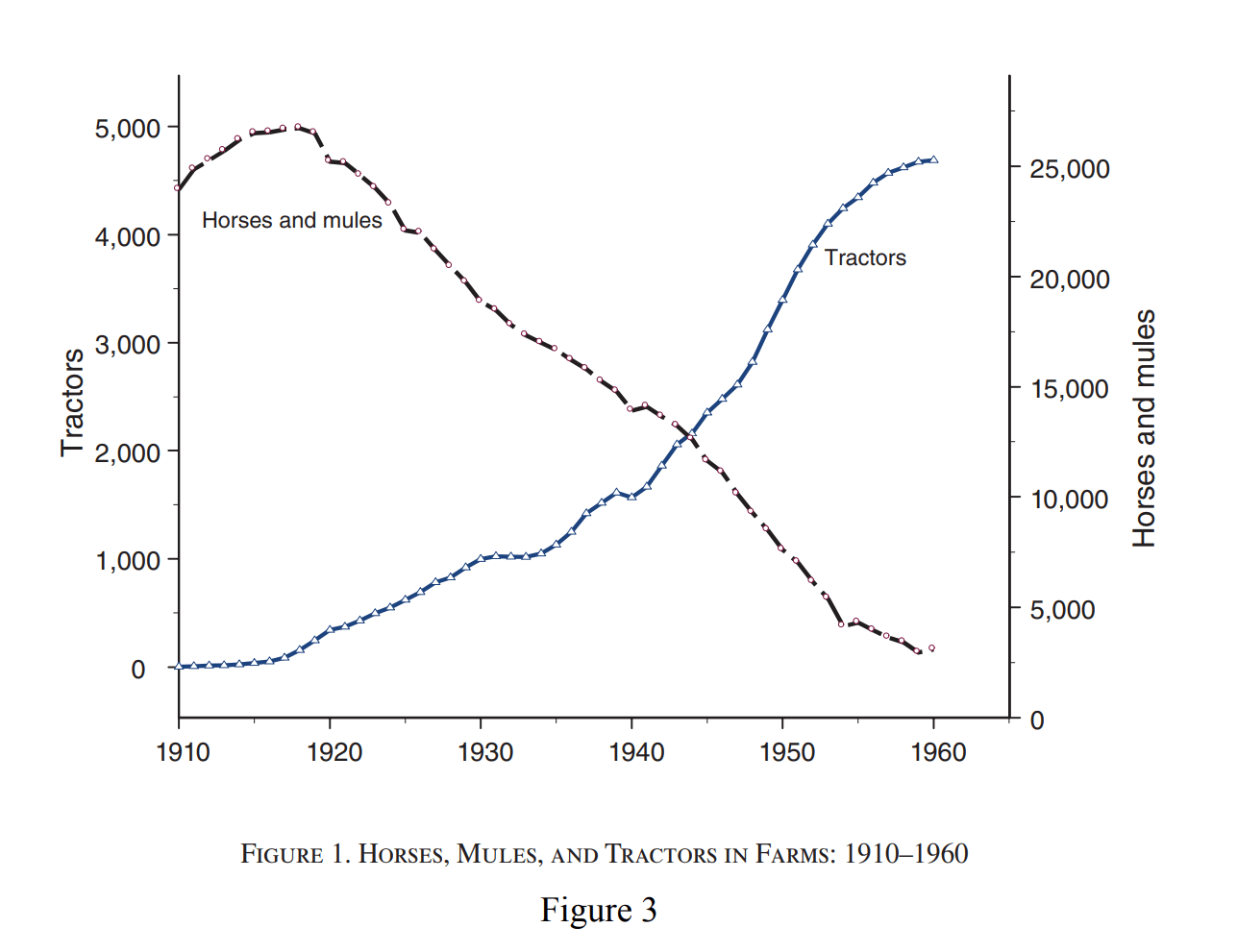

The image I was looking for was this:

From another paper on technological diffusion:

We highlight first that the locations where economically impactful technologies are developed are geographically highly concentrated, with a handful of urban areas contributing the bulk of the early patenting and early employment within influential new technologies. One striking figure is that 56% of the pioneering locations for the most economically impactful technologies are in two parts of the U.S. – Silicon Valley and the Northeast Corridor. Second, despite this initial concentration, jobs relating to new technologies spread out geographically. But this rate of diffusion is extremely slow, happening over several decades rather than in just a few years. Locally developed technologies continue to offer long-lasting benefits for jobs in their pioneer locations for multiple decades. Third, jobs relating to new technologies are highly skill biased – 57% of the initial jobs associated with a given new technology require a college degree. Over time, the mean required skill levels of the new jobs decline, albeit at a very slow pace. Fourth, low-skill jobs associated with the use of a given new technology spread out geographically significantly faster than highskill ones, so that the pioneer locations where the technology was invented host a disproportionate share of high-skilled jobs relating to that new technology for several decades after its year of emergence.

Combined with the extreme spatial concentration of the most economically impactful innovations, this pioneer advantage engenders large and persistent regional disparities in economic opportunity, giving a handful of U.S. locations a lasting advantage in high-skill jobs.

Adam Butler is one of the most thoughtful people I follow in finance, and I always find his perspectives interesting. Here’s his latest on the AI cycle:

I’ve got bad news.

The AI cycle is over—for now.I’ve been an unapologetic AI maximalist since the first time I tricked GPT-4 into writing a working Python back-test for a volatility strategy back in early 2023. I’m still convinced it will take the wider economy years—maybe decades—to fully digest the productivity shock we’ve already uncorked. But the curve we’ve been riding just flattened into a long plateau.

The problem isn’t that the models stopped improving. It’s that the improvements we need are measured in orders of magnitude, not percentage points. Every step up the scaling laws now demands a city’s worth of electricity and a sovereign wealth fund’s worth of GPUs. You can still squeeze clever tricks out of mixture-of-experts or chain tiny specialists into something that looks like agency; that keeps the demo videos cinematic. It just doesn’t get us to super-intelligence. For that we need either an architectural miracle (unforecastable by definition) or a civil-engineering miracle (a decade-long sprint to build nuclear plants and 2-nanometer fabs). The first is luck. The second is politics. Both are scarce.

Join the Conversation

Share your thoughts and go deeper down the rabbit hole