Came across this fascinating paper looking at whether developing countries are catching up to advanced countries. It’s frankly depressing, but I asked Claude for a summary.

What Remains of Cross-Country Convergence? A Critical Review of 50 Years of Economic Growth Research. Summary by Claude.

This comprehensive 2020 review by Paul Johnson and Chris Papageorgiou examines one of economics’ most enduring questions: Do poor countries eventually catch up to rich ones? After analyzing five decades of research and data, their conclusions challenge popular narratives about global economic convergence.

The Convergence Hypothesis: A Simple but Elusive Concept

The convergence hypothesis, rooted in Robert Solow’s 1956 growth model, suggests that initial economic conditions shouldn’t matter in the long run—poor countries should grow faster than rich ones and eventually catch up. This idea has generated thousands of academic papers and influenced development policy worldwide. The theoretical foundation rests on diminishing returns to capital, which should slow growth in rich countries while poor countries benefit from technology transfer and “catch-up” effects.

What the Data Actually Shows

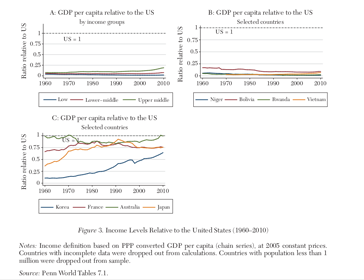

The authors analyze comprehensive data covering 182 countries over 50 years, revealing a complex picture that defies simple narratives. Global GDP per capita grew from $4,155 to $13,368 between 1960 and 2014, representing an impressive 4% annual average growth rate. However, this aggregate progress masks enormous variations across countries and time periods.

Regional performance tells a story of dramatic divergence rather than convergence:

• East Asia: Sustained growth averaging 3-4% annually over five decades • Sub-Saharan Africa: Poor performance until 2000s recovery (1.8% growth) • Latin America: Devastating negative growth (-0.6%) during the 1980s “lost decade” • South Asia: Accelerated from 1.6% growth (1960s) to 4.5% (2000s)

The convergence reality check reveals sobering truths about global economic development. Despite decades of research and policy interventions, poor countries as a group have not closed the income gap with rich countries. In many cases, income disparities have actually widened over time. The evidence instead points to “club convergence,” where countries converge only within similar groups, such as OECD nations converging among themselves while remaining distant from developing economies.

Key Findings Challenge Conventional Wisdom

Perhaps the most striking discovery is that economic growth is highly episodic rather than smooth and predictable. Growth rates in one decade serve as poor predictors of performance in the next decade, with correlations often negative for low-income countries. This pattern suggests that many countries experience “start-stop” growth rather than steady progress toward prosperity.

The data reveals three distinct country clusters rather than evidence of smooth convergence toward a common income level. High-income countries have actually seen their growth rates decline over time, middle-income countries face potential growth slowdowns in what economists call the “middle-income trap,” and many low-income countries remain trapped in persistent stagnation despite global integration.

Heterogeneity emerges as the defining characteristic of modern economic development. The variation in development prospects is staggering:

• Vietnam and Laos: Could reach middle-income status within 3-4 years • China: Transformed from worst performers (1960s) to best (1990s-2000s) • Fragile states: Average 2% lower annual growth than stable low-income countries • Niger: Would require over 700 years to reach middle-income status at current growth rates

Global Inequality: A Nuanced Picture

While country-level convergence remains elusive, examining individual-level global inequality reveals a more complex story. Global inequality has actually fallen since 2000, largely driven by China’s historic growth that lifted millions from poverty. This progress has created an emerging “global middle class” with incomes between $5-15 per day, representing a significant improvement from previous decades.

However, these aggregate improvements mask persistent challenges. The bottom decile of the global population saw minimal income gains between 1988 and 2011, while many fragile states proved unable to participate in the broader growth acceleration experienced elsewhere. Meanwhile, within-country inequality has increased in many nations, creating a paradox where global inequality falls even as domestic inequality rises.

Policy Implications and Future Outlook

The authors’ analysis carries important implications for development policy and economic theory. The absence of automatic convergence suggests that small-scale policy interventions may be insufficient if countries are trapped in different development trajectories. Large-scale institutional and policy changes may be required to fundamentally shift a country’s growth path, challenging the “one-size-fits-all” approach that has dominated development thinking.

The study also questions recent optimism about African and emerging market growth. Much of the progress observed in the 2000s may reflect the removal of previous inefficiencies rather than the establishment of sustainable growth engines. These improvements often represent “one-off level effects” that don’t guarantee continued growth, particularly as commodity price booms that supported many developing economies have begun to fade.

Rather than simply testing whether convergence occurs, the research community should focus on:

• Understanding mechanisms that promote or hinder catch-up growth • Investigating why growth proves so episodic in developing countries • Identifying specific conditions under which convergence clubs form • Developing more realistic models of global development patterns

The Bottom Line

After reviewing extensive evidence spanning multiple methodologies and decades of data, Johnson and Papageorgiou conclude that optimism about rapid, broad-based convergence is “unfounded.” While some countries have achieved remarkable catch-up growth, convergence is neither automatic nor universal. The global economy appears characterized by multiple equilibria rather than a single convergent path toward shared prosperity.

This assessment doesn’t diminish the importance of development efforts, but it demands that such efforts be grounded in realistic expectations about the challenges of sustained economic growth. The dream of global economic convergence, while compelling in theory, remains largely unrealized after five decades of unprecedented global integration and development assistance. Understanding this reality may be the first step toward more effective approaches to promoting global prosperity.

CEPR summary brief and another one from AEA.

Join the Conversation

Share your thoughts and go deeper down the rabbit hole